- Home

- Clara Kramer

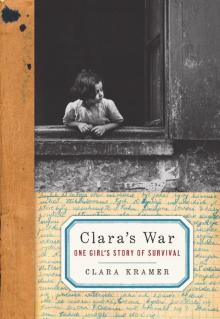

Clara's War

Clara's War Read online

Clara‘s War

One Girl’s Story of Survival

Clara Kramer with Stephen Glantz

For my parents,

who taught me compassion and decency;

for my little sister,

who showed me true bravery;

and to the Becks,

who saved my life and restored my

faith in mankind

And you shall teach them diligently to your children, and you shall speak of them when you sit at home, and when you walk along the way, and when you lie down, and when you rise up.

Deuteronomy 6:4–9

Contents

Epigraph

A Note to the Reader

Prologue

1 My Grandfather

2 A Place to Hide

3 The Housekeeper

4 A Gift from Mr Beck

5 I Go to the Ghetto

6 The Final Solution

7 The Arrival

8 18 April

9 The Love Affair

10 Days of Awe and Atonement

11 A Year Underground

12 Valentine’s Day

13 The SS Move In

14 We Are Just Starting to Suffer

15 I’m Losing Hope

Photographic Insert

16 The Exodus

17 Zolkiew without Mania

18 The Diary

Epilogue: Life Goes On

Acknowledgements

About the Author

Credits

Copyright

About the Publisher

A NOTE TO THE READER

Writing this book was like walking out of my kitchen door in Elizabeth, New Jersey, and straight into my home in Zolkiew. Although the events in this book happened over 60 years ago, they have never left me. As with many survivors, I relive them in the present.

I am 81 years old, and I am one of the lucky ones. Ever since the day I left the bunker, I have done my best to live a worthy life. I have dedicated myself to the teaching of the Holocaust. The privilege of surviving comes with the responsibility of sharing the story of those who did not.

Everything in this book is as I lived and remember it, although I have taken the liberty of reconstructing dialogue to the best of my recollection. I have also used the spelling and names most familiar to me. During the 18 months I spent in the bunker I kept a diary which today is in the Holocaust Memorial Museum in Washington DC. There was little light and less paper and only one nub of a pencil to write with. I documented as much as I could in my diary, but although I often spoke about my life, the idea of writing it never occurred to me. Thank you to Stephen Glantz for encouraging me and for taking this journey with me back to Zolkiew. And thank you for capturing my life so beautifully on paper. I am so grateful that my great-great-grandchildren will be able to meet those of us who came before.

From my memory to theirs, and to yours.

Where the beginning of a chapter is in italics, it is an extract from my diary.

Clara Kramer

PROLOGUE

1 September 1939

My entire family was camped out on blankets and goose-down bedding in the apple orchard behind Aunt Uchka’s little house. Out of all my aunts, Uchka was my favourite. Not even ten years older than me and not much taller, she was more like a best friend. Zygush, her three-year-old son, scampered about the orchard picking up fallen green apples. His father Hersch Leib was on his heels, but only managed to catch his shadow. After 20 minutes or more, Uchka finally intervened, handing her little baby Zosia to Babcia, my grandmother, and reaching out to capture the laughing boy as he ran by.

Zygush didn’t understand that he shouldn’t be laughing or running or having a good time. He would only be quietened with the traditional bribe of a cookie. For him it was just a night-time picnic like those we enjoyed on Paradise Hill. He didn’t know that Poland had been invaded by the Nazis that morning while we had been sleeping. Poor Mr and Mrs Gorski’s house, on the outskirts of town and surrounded only by ripening rye and wheat fields, had been bombed. There were still planes flying above us headed for Lvov just 35 kilometres away. Even though the noise of the engines was deafening, none of us said a word. In my 12 years of life, I could not think of another time my family had sat together in silence. But we were all petrified that the pilots might hear us and attack us instead. When my restless little sister Mania had run out from under the apple tree to get a better look, Mama hadn’t dared raise her voice and had had to resort to feverish gestures to get her to sit back down.

I didn’t know who had first come up with the idea that we should all sleep outside, but the idea had travelled faster than gossip up and down our streets. After what had happened to the Gorskis we were afraid to stay in our homes. We had rummaged the closets for our old feather beds, which Mama and Babcia decided could get filthy. After we had packed up some bread, fruit and cheese, the nine of us who all lived together in the same house had walked the kilometre to Uchka’s. Our town seemed to have been spilt in two. One half, loaded with blankets and food, was making an exodus, while the other half stood staring, dazed, wondering if they should join us. As we passed near the Gorskis’, I was filled with a morbid curiosity. I had never seen a bombed-out house before and wanted to go and look at it, but Mama wouldn’t hear of it. She didn’t want us separated. In typical fashion Mania had ignored her and already run ahead to Uchka’s, while I was stuck walking at a snail’s pace. Babcia and Dzadzio, my grandparents, who were portly and only walked distances in considerable pain, kept telling us not to worry about them and go on already. But Mama didn’t want her parents to be alone if there was another bombing.

Mama was nicknamed Salka the Cossack because she went through life as if she were mounted on a horse, wielding a sword at any of life’s problems. She could manage anything from her kitchen table. But no matter how much we talked and talked and talked, trying to make sense of the new reality, today was a day of questions without answers.

Across the fields and in all the pastures and farms surrounding our small city of Zolkiew, dozens of other families were getting ready to sleep under the stars. Even though it was a warm September night, with the air fragrant with the scent of newly mown hay, no one could sleep. But eventually exhaustion had triumphed over fear and, in ones and twos, everyone but me had succumbed. I had never been a nervous and anxious girl; I was the quiet, studious daughter. But as I watched and listened for more planes to come, I felt I would never be able to sleep again.

In the distance I could make out the silhouettes of Zolkiew’s baroque church spires with their pregnant onion tops and golden domes. Not a light was on, and my familiar town looked eerily deserted, almost haunted. It felt as if the war’s shadow had physically darkened our town. Our family had been here in this corner of Galicia in south-eastern Poland for ever. I couldn’t imagine living anywhere else. We had been rooted here longer than most of the white birch and the Russian pines that formed the islands of forest in the steppe. I had never heard Dzadzio and Babcia speak of another place in our family’s history.

As long as I could remember, my family moved and lived in a pack. You couldn’t turn around in our little stone house without bumping into somebody. Now, spread out under the apple trees, sleeping in piles, huddled together on the feather beds, using each other as pillows, we resembled a pack more than ever. The only one missing was Aunt Rosa, who lived in the thick forests of central Poland. When Aunt Rosa had got engaged to her husband Pinchas, Babcia had gone into mourning. Rosa was the prettiest of the sisters and Babcia had always said she could have had any man she wanted in town. It wasn’t that Pinchas, a timber merchant, wasn’t a catch any mother wouldn’t brag about, it was because he lived on the other side of Poland in Josefow and she would have to leave

Zolkiew.

Next to me, my little sister Mania, tan from the summer sun, slept. She was the first to drop off and was asleep even before the little ones. And asleep was the only time she was ever still. At ten she was faster than most of the boys her age and her thin arms and legs were as strong as the braided wire the peasants used to bale their hay. The skipping rope that she always wore round her neck like a necklace lay next to her. On the other side of Mania was my aunt Giza, Mama’s second youngest sister. An amateur actress, she looked like the star of a silent movie. When Giza was on stage, playing some tragic figure, she would ring her sable eyes with kohl and paint her lips red. But real tragedy had struck Giza off the stage. She became a widow at 33. When she left to go to her husband’s birth town of Vienna for yahrzeit, she ended up staying there for a year.

When Giza finally came back to Zolkiew and moved in with my grandparents on the other side of the house we shared, all Babcia wanted was for her to find another husband. But instead of having grandchildren, Giza had started an undergarment business. ‘Of all the fachoted, crazy, ideas!’ Babcia had said. ‘You’ll fradrai dich den kop, you’ll give me a knock in the head! When the new dress doesn’t fit, they’ll blame you!’ Babcia had been especially appalled and embarrassed when Giza had put a sign in our front window. The women didn’t just come to buy a girdle. They sat. They had tea. They had pastry. They talked. Then they bought. Then they sat some more. Our house had become Giza’s factory, showroom and café all in one. Zolkiew at the time had a large regiment of Polish cavalry stationed at the castle and soon our front room was filled with officers’ wives. Once word got out that even the Polish nobility was wearing Giza’s products under their gowns, she couldn’t make them fast enough. Of course, despite the ranting, Babcia became Giza’s best customer, closely followed by her sisters. And soon she was boasting that anyone who was anybody in Zolkiew wore a girdle by Gizela, which was Giza’s given name, and much more sophisticated than the diminutive everyone called her by.

Spread out next to Babcia, Dzadzio was snoring loudly. Even though I knew my dzadzio was ancient, he seemed whole and hearty in my eyes. I adored him. When I got my report cards, I would run home to show them to Dzadzio first. He would pick me up on his lap and cluck his teeth and shake his head and say, ‘Clarutchka, Clarutchka, what am I going to do with you? Zeros again?’ I had never got anything less than an A in my life and I knew this was his way of praising me. Dzadzio still went to minyan every day, but the rest of the time he would sit in his big chair by the window and watch the world go by.

Dzadzio had passed on his part of the ownership of the oil-press business, which we shared with two neighbouring families, the Melmans and the Patrontasches, to my father. The men’s wives, Fanka Melman and Sabina Patrontasch, were friends with Mama. They shared everything, including a housekeeper, Julia Beck, who was as good at cooking Jewish as Mama. Mama and Klara, Mr Patrontasch’s widowed younger sister, had even nursed together as infants at the breast of Julia’s mother, who was their common milk mammy and our grandparents’ housekeeper. Klara and Julia had been raised together like sisters and were the best of friends.

Under the tree near Dzadzio were my uncles Manek and Josek, who also lived with us. I adored them both. Mama said that Josek, with his deep blue eyes and golden hair the colour of silk in lamplight, was the Don Juan of the family. Dzadzio followed Josek around like his conscience. Mr Patrontasch had a lovely 17-year-old sister, Pepka, whom Josek would talk to across the fence for hours at a time. In our little town, when a boy talked to a girl more than twice, their parents would run to get the shadkhyn, the matchmaker, and start working out the marriage contract. When Dzadzio, sitting at his habitual place by the window, couldn’t take it any longer, he would walk out and drag Josek away, yelling at his son: ‘Are you going to send that girl up the chimney or marry her?’ He didn’t want his son to send their neighbour’s daughter’s reputation up in smoke.

Manek was the complete opposite of Josek, an ardent Zionist who supported a little kibbutz that some of the young people in Zolkiew formed. Mania loved to follow him around and would go along with him to many of the meetings of the kibbutzim. She was at the kibbutz so often that somebody once asked her if she was going to be a kibbutznik when she grew up. She laughed at the absurdity of the question. ‘Are you crazy? There’s a whole wide world to explore!’ It was Manek who had taught us how to dance. Whenever there was a wedding, Mama, her sisters, all the girls in Zolkiew were lucky to get a dance from Manek because we tried to keep him to ourselves.

Uchka’s wedding had been beautiful. Since Uchka was the youngest of the Reizfeld sisters, the tradition was to throw a huge party. My grandparents didn’t skimp. Rosa came with her husband Pinchas Karp and their four children, Wilek, Frieda, Klara and Mania. It was traditional for parents to name their children after departed parents and grandparents, which often resulted in duplicate names among cousins. In our family we had two Zygushes, two Wileks, two Gizas, and even a third Mania. But nobody in the family was ever confused and none of the children felt like we were wearing hand-me-down clothes. Like everything else in my life before the war, this made perfect sense.

Uchka and Hersch Leib looked like they were no older than 16 as they stood under the chuppah. Whenever there was a Jewish wedding, the poor of Zolkiew, or any town in Poland for that matter, knew they would be welcome. There was a long table on one side of hall reserved for anyone who wanted a good meal. Mama had hired a modern band from Lvov that played tangos and waltzes. I danced with all my uncles and cousins. But Mania and I monopolized Manek for most of the evening. We might have let him dance once or twice with the bride and his sisters. Before the end of the evening, Uchka’s brothers and some of the other young men danced around the hall with Uchka in a wicker throne mounted on their shoulders. The newly married couple then left, way before the other guests. They weren’t going on a trip, they were going home to spend their wedding night in Dzadzio and Babcia’s room, where Mama and Papa and all the other sisters and their husbands had spent their first night together. My grandparents had a massive bed where we had all been born. Everyone from Mama to her brothers and sisters, Mania and me, and most recently Zygush and Zosia, had been born in that dark mahogany bed. Promptly nine months after the wedding, Zygush was born.

That had been only three years ago. Now, instead of getting ready for the coming school year and gossiping with my friends, we were getting ready for a war.

It had been brewing for a long time. We had been listening to the ranting speeches of Hitler on Dzadzio’s radio for years now. Even though they could understand every word, Mama and Papa didn’t believe anyone that extreme could rule for very long. They were convinced that the German people would rise up and overthrow him. But against their expectations, Hitler continued to gain power. Despite the mounting anti-Semitism all across Europe, my parents didn’t believe that the tragedy of Nazi Germany would reach us in Zolkiew. Our town had a tradition of tolerance that dated back to Jan Sobieski, the legendary king of Poland, saviour of Europe, who had defeated the Turks in the Battle of Vienna. His family had made Zolkiew its official residence in the 16th century.

I was proud to be part of the Sobieski tradition and I liked to think that his Enlightenment ideals were still alive in our town. Zolkiew had dozens of political and religious organizations: Zionist, Hassidic, Orthodox, Communist, Bundist, Socialist and others. Jewish life in Zolkiew was shtetl life, a thick soup of schools, synagogues, charities, clubs and fraternal organizations. The customs and traditions nourished us but also gave us plenty of indigestion. Papa always said we were five thousand Jews with ten thousand opinions! We were always at war with each other over one thing or another, but our city was nevertheless something of an oasis in the anti-Semitic Eastern Europe.

For over a year now, since shortly after Germany had taken over Austria, our town had been filling up with refugees. There was barely a room or a flat that had not been taken. The Joint Committee for Welfare sup

ported over 200 refugee families. There were two meals a day for more than 640 children. We did our share too. Every Wednesday at noon the Herzbergs, a very nice refugee couple from Vienna, came to our house for lunch. Over Mama’s chicken soup served on the special china, the Herzbergs told us about the nightmare they had left behind. They told us how their synagogues were destroyed. How Jews were beaten in the streets and how shops and businesses were looted. They were very clear about what Hitler meant for Jews.

Last year, Uncle Manek had suggested for us all to emigrate to Palestine. He said that the world was on fire. When a large Ukrainian company wanted to buy the factory, Manek had begged Papa and Dzadzio to sell, saying that this was our chance, but they had refused. Dzadzio was so mad at Manek for wanting to sell his life’s work that he had to live on our side of the house for a while. Manek never brought it up again. He didn’t have to.

Not even a week ago, the Russians and Nazis had signed the Molotov-Ribbentrop non-aggression treaty. Papa had explained to me that it meant that Nazi Germany could now invade Poland and open an eastern front and the Russians would do nothing to stop them. The pact stunned all of Poland. No one could understand why Russia would relinquish their historical designs on our country. It was as if Stalin were handing Hitler Poland like a goose stuffed for the oven. After having been brutally occupied by the Tsar and the Russian Empire on and off for close to two hundred years, we had feared the Russians more than the Germans. But that was changing with Hitler. Most of Poland’s defences were directed at the eastern border with Russia. We wouldn’t have the time or the resources to defend our western border.

Clara's War

Clara's War